CZECH IT OUT!

Translating the Czech artist Vojtěch Kubašta’s movable and pop-up books and the History of Pop-up books

by Ellen G.K. Rubin

(reprinted from Book Source Monthly; October, 1999; Vol.5, No.7)

Don’t get me started about how I am only able to speak one language, and how remiss America is by ignoring the innate ability of most children to become bilingual. I can only speak English—period. Now, with that understood, let me tell you about my attempts to translate an illustrated book by the Czech artist, Vojtěch Kubašta.

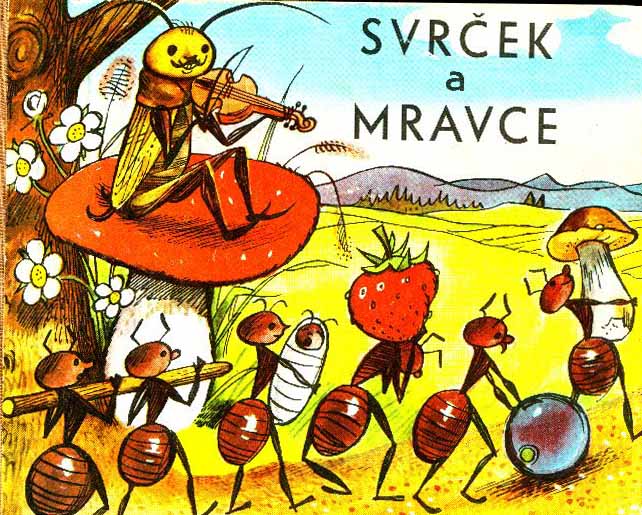

When it comes to books illustrated and paper engineered by Kubašta, I am like a pig seeking truffles. (I’ll explain why later.) After all, I am a collector of pop-up and movable books, first and foremost. So enamored am I with Kubašta that when I recently found his book with ‘pierced’ boards allowing the reader to see through to the next page, I couldn’t pass it up. It’s title, Svrček a Mravce, (The *Grasshopper and the Ants), is evident from the illustrations, wonderfully anthropomorphic and richly colored. The language appeared to be Czech. Although I keep a Czech dictionary handy, I could not find in it words from the title or from the text. What was I to do? I don’t know anyone who speaks Czech.

About this time, at a local restaurant, I was served by a waitress with an accent I couldn’t place. “What is your native language?” I asked, envying her bi-, or possibly more, lingual ability. “Hungarian,” she said, with a hint of paprika. Hungary is near Czechoslovakia I reasoned. Maybe my book is written in Hungarian. She agreed to my stopping by to have her determine the book’s language. But it wouldn’t be that easy. When I showed it to her, she knew immediately it wasn’t Hungarian, politely tolerating my ignorance. She thought the text looked Romanian. Romanian!! I know a Romanian couple, architect friends of my brother-in-law.

I called Mihai and simultaneously faxed him copies of the front and back covers. I could feel the thrill of success at hand. He was delighted and surprised to have all of this appear on his fax machine amid the blue-lined drawings and pages of building codes. “But no,” he said sadly. “It is not Romanian. It looks Serbian.” Serbian??!! I don’t remotely know anyone who speaks Serbian, now feeling lost in the Tower of Babel. “I’ll have my wife, Donna, show it around her multi-national office.” he offered. “Maybe someone there can help.”

Dejection. A sure dead-end. Then, I remembered last year I had purchased a Kubašta pop-up from a Czech dealer at the New York ABAA show. And, as collectors’ habits would have it, I had kept his card. I e-mailed him and faxed the copies. And waited. Within two weeks, Zybynik Groh, of Art…on paper, responded by e-mail, “Here is the solution to your puzzle.” The book was Slovakian!!, a language very close to Czech. It had been published in Bratislava, the current capital of the Slovak Republic, by Mladé letá, “Slovak publishers for the youth.” Zbynik told me he had never seen a Kubašta like this one.

Finally, my quest had me seek out Michael Dawson, an English authority on Kubašta. Since this book does not appear on Dawson’s Kubašta bibliography, I wondered would he know of it. A fax flew again across the ‘Pond’. Although Michael’s list already had a “pierced” book from 1959, this one, from 1958, was new to him. He was delighted to add it to his ‘check-list’ stating, [The Grasshopper and the Ants] “must be one of Kubašta’s earliest children’s book efforts.”

Whew! My simple question had been answered in the most roundabout way. But in the end, I learned what I needed to know, had brought delightful surprises to some, gave new knowledge to others, made new friends, and had reacquainted myself with old ones in the process. And all with just the English language. Imagine that!

If Vojtěch Kubašta, artist, illustrator, and paper engineer, is not known to you, I need to introduce you to him so that you may understand my passion and, hopefully, come to appreciate his work. The term, paper engineer, describes an artist who either makes illustrations three-dimensional and leaping off the page, or movable, activated by tabs, flaps, or wheels. While little has been written about Kubašta, and details about his personal and professional life are sketchy at best, his movable books, produced largely after 1960, are familiar to pop-up book collectors and dealers.

Born in Vienna, Kubašta studied architecture in Prague, graduating in 1938. During the war, he eked out a living as an illustrator. Most impressive from this time are the series of hand-colored lithographs of historical, architectural landmarks in Prague done with historians, Zdeněk Wirth and Dr.Otakar Štorch-Marien. Their folio format , with loosely inserted bound text, foreshadowed the panascopic series of pop-ups to come later.

Kubašta continued to illustrate children’s books for the State Publishing House, as well as movie posters and lobbycards for American movies which managed to get through the Iron Curtain. Publishers were able to take advantage of the older, slower printing presses not destroyed in the wars, as they had been in England and Germany. The result was richly vivid illustrations, seemingly saturated with ink. Kubašta’s faux-naif style with a Bohemian flavor is somewhat exotic to an American eye. Throughout Kubaštsa’s stories are the anthropomorphic animals, dwarves, puppets, and wizards Kubašta collectors love. Since I don’t read Czech, it is a testimony to his talent that I appreciate the stories without the text.

In the late 1950s, Kubašta’s work took a major shift. It is not known specifically what influenced him to experiment with movable illustrations, but with an architect’s eye for three dimensions, a graphic artist’s talent for illustrating, and a cultural bias towards puppetry and folk tales, Kubašta possessed all the elements to uniquely construct pop-up books. His books were mostly large double-page pop-ups with text printed parallel to the spine. His genius was to take a single sheet of cardstock and cut and fold it so that at least four dimensional layers were formed. For some illustrations, additional pieces were added which could be moved with a tab. The large “Panascopic Model Book” was a tri-fold with the last cardstock page unfolding to create a three-dimensional model standing almost 12 inches tall! Text pages were stapled inside, much like the earlier historical portfolios.

Through Artia, a state-run export company, the English company, Bancroft, imported Kubašta’s books, exported millions around the world translated into thirty-seven languages. Even the cartoon classics of Walt Disney were interpreted into pop-ups by Kubašta. Besides approximately 125 pop-up titles, Kubašta had also produced by the time of his death at 78, a series of pop-up souvenir postcards, a counting series, and illustrated books of classical titles, including Till Eulenspeigel. Yet, despite this great prolific outpouring, Kubašta remains relatively unknown outside of Prague. I hope you’re curiosity is tweaked to check out his work.

The question remains why should such an accomplished and innovative artist go unrecognized? Perhaps Kubašta’s relative obscurity may be attributed to the fact that these pop-up books were cheaply made and sold for relative pennies, never garnering the serious attention of adults. Or as today’s most artistic paper engineer, Robert Sabuda, laments, [pop-up books are] “the stepchildren of children’s books.” In architecture, artistry in three dimensions is expected and lauded. The same respect is not applied to paper engineering…but it should be.

One explanation for this lack of regard could be that children’s movable books are the relative “newcomers” to the printed word. Until the mid-18th century, there were few books of any kind intended just for children, let alone for their entertainment. The young were expected to quickly join the ranks of the adults and few accommodations were made by way of toys, clothing, or household effects. Movable books did exist, however, from as early as the beginning of the 14th century in the form of volvelles (movable circles of paper pierced with string) in tracts on astronomy, astrology, and anatomy.

The true movable children’s book was designed around 1765 by the Englishman, Robert Sayer, and called turn-up or metamorphosis books, or harlequinades, after the popular pantomime character, Harlequin. This first ‘book as toy’ was made by folding a single sheet of paper. The story would progress by turning the folded illustrations up or down covering an existing illustration and changing it. What rapidly followed were tunnel books, peep shows, paper dolls, and the like, ushering in, by the end of the 19th century, the “Golden Age of Pop-ups”. The publishers, Dean and Sons, Raphael Tuck, and Ernest Nister, filled the market niche, created by the newly formed Victorian leisure class, with beautifully illustrated books chromolithographed mainly in Germany. McLoughlin Bros. did the same in the United States.

Lothar Meggendorfer (1847-1925), illustrator and paper engineer, is considered the most innovative paper engineer. And deservedly so. Meggendorfer, of Munich, animated his sophisticated , often comic, illustrations using specially designed rivets around which levers effected multiple and simultaneous movements, all by pulling one tab.

World War I rang the death knell for pop-up productions due to diminished access to German printing, and shortages of paper and labor. Between the wars, pop-ups were produced primarily by S. Louis Giraud of England whose singular contribution was the invention of the first true pop-up, one rising up off the page. Blue Ribbon Press of New York co-opted this technique and patented the term, ‘pop-up’, in the 1930s.

Enter Vojtěch Kubašta, creating uniquely designed pop-ups in the late 1950s. In the early ‘60s, Waldo (Wally) Hunt (1920-2009), an American advertising entrepreneur, saw Kubašta’s books and wanted to bring them to America. But the Communist Party bosses would not fit an initial order of a million copies into their Five Year Plan! Wally’s company, Graphics International, inspired by Kubašta, sold Random House and Hallmark on the idea of pop-up books for children. The rest, as they say, is history. Almost single-handedly, Wally Hunt, now of Intervisual Books, launched the “Second Golden Age of Pop-ups”, which is in full swing today.

Those of us who love language also love books. Reading a pop-up book can be like a succession of exploding firecrackers, ascending through our senses from the quiet voice on the page to the visual expansion of the illustration to, finally, the penultimate, an illustration alive in three dimensions. The resulting emotion is joy; the “WOW!” effect. Vojtěch Kubašta rarely fails to have that effect on me. Searching out and translating his books remains a labor of love.

* I have since learned the correct translation is-Cricket.