Ephemera-An Erotic Watchpaper

From The Ephemera News, Vol. 29, No.4, Summer 2011 [but with additional images]

Watchpapers: Practical Tokens of Labor and Love

by Ellen G. K. Rubin

The dealer took his stubby finger to the 2” paper disc and lifted the harem dancer‘s delicate paper leg allowing “the light to shine where no light had ever shone before.” Underneath her flowing pantaloons, she was stark naked! Frankly, I blushed but he couldn’t see it since we were in a dimly lit corner of Papermania in Hartford, CT. As any collector would, I held my tongue and my breath. How much would he want for this “gotta have” movable piece of ephemera? And what was this disc anyway?

But let me take a brief moment to introduce myself, as this is my first article for The Ephemera News. I call myself The Popuplady and have collected pop-up and movable paper objects for over 25 years. I began with mostly children’s books and those in science and medicine, particular interests of mine. After reading two Random House pop-up series books to my young sons, I was immediately hooked on this unique interactive form of learning and entertainment.

These books were the first I had ever seen of the pop-up book genre. In 1987, in the hopes of filling the looming “empty nest,” I returned to school for further study. While in New Haven, CT for the Yale program for Physician Associates, I heard of a new exhibit at the Sterling Library on campus. The exhibit was called, “Eccentric Books,” and I took the time from my overwhelmingly busy schedule to visit it twice.

I was amazed to see more than 125 pop-up and movable books. The earliest was Johannes Mueller’s,Regiomontanus, Kalendar from 1474 with a volvelle. A volvelle is a disc of paper with a pointer at its edge or die cut holes that allow information to show through from the base page. By moving the disc or wheel, information is collated or calculated. The volvelle has been traced back to the 13th century, but that’s another article. [see The Popuplady’s Smithsonian lecture on the 700+ years of movable books] TheRegiomontanus, and the other Renaissance books on anatomy and astronomy at Yale, opened my eyes to the depth of scholarship I had yet to acquire. The hook sank deeper into my collector’s gut.

After graduation, I began collecting in earnest, acquiring along the way, examples of movable ephemera. These included postcards, trade cards, advertisements, annual reports, premiums and promotional objects, invitations, and theatrical programs, to name but a few. Unlike my collection of over 7000 books that is cataloged using FileMaker Pro, my 25 5” binders of ephemera remain mostly un-cataloged.

In the last few years, as my ephemera collection expanded, I began to notice that the paper engineers—those artists who create movable illustrations and until now, remained mostly unnamed—took greater risks with mechanisms in ephemera than in they did in books. As subject matter played a smaller and smaller part in my collecting strategy, my interest in the complexity of the mechanisms grew. I joined the Metropolitan Postcard Club of New York City and The Ephemera Society to learn more. I already was a charter member ofThe Movable Book Society. Visitors to my library are now more likely to be shown items in my binders, wowing them with the papers’ intricacies. For example, it continues to astound me that postcards with pop-ups survived the rigors of going through the mail. It has become more difficult to find pop-up and movable books not already in my collection, but movable ephemera are still out there for me to uncover.

With this acquisitive mind-set, I had arrived early to the Papermania Show determined to have first dibs on movable paper objects. I spied the circle of paper in a glass showcase, flagging this as a precious and delicate. I could make out finely drawn lines and rich colors, probably applied by hand. My excitement spun into orbit when I read the tag lying by the disc. It said, “Lift skirt.” This was the most promising sign that the item could be movable! But my gratification would be delayed. The dealer was nowhere to be found. This object was totally intriguing, and I twitched in anticipation of having it in my hand…and maybe in my collection. I visited several booths before scurrying back to the dark corner.

The dealer opened the case and put the fragile disc in his large hand. He told me that it was a watchpaper used to protect the mechanisms of pocket watches from dust. From the second half of the 18th century until about mid-19th century, paper was used in the watches. He gave me a brief history of a genre I knew nothing about. The artwork of the Salome-like harem dancer leaping with flowing scarf in a majestic hall was exquisite. The fact that she was bluntly naked when the leg was lifted just made her that much more exotic. We agreed it was most likely mid-19th century and negotiated a price, which I eagerly paid. I kept my glow of discovery and ownership throughout the rest of the show. The watchpaper was definitely the find of the day!

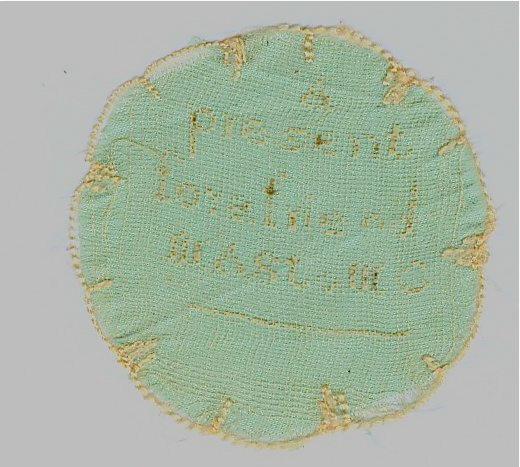

I couldn’t wait to get home to start my research. I immediately pulled down from my reference shelf, The Encyclopedia of Ephemera, and read a description of watchpapers. [The spelling complicates all efforts to research: watchpapers, watch papers, watch-papers.] The Encyclopedia, without giving the earliest examples, described their development as moving in parallel with the progress in printing. In the early 18th century, watchpapers were made of “blank discs of paper or fine linen.”1 In the mid-18th century they could also be crocheted or printed on silk and then ornately embroidered. There are examples with fringes and sequins! A few like mine were hand painted.

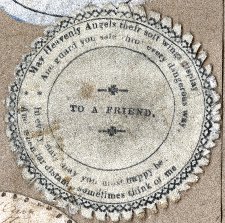

As the dealer had correctly told me, watchmakers and their repairers inserted the discs into the backs of pocket watches. Often they were used as packing to protect the works.2 As printing became more sophisticated and could be produced more cheaply in quantity, the watchpapers were used as trade cards with advertising and sometimes love-notes, memorials, or birthday greetings. They often recorded repairs just as somewhere on your car there is a sticker from your mechanic dating when he last changed the oil.

In addition to the name and address of the shop, watchpapers often had “classical and allegorical figures” such as Father Time, printed or engraved or drawn by hand. Aaron Willard, from a notable American watchmaking family, had a watchpaper engraved by Paul Revere in 1781. The image is considered typical of Revere’s style. It is 1 7/8 inches and, in addition to Father Time, has other temporal images, such as Fame holding a bugle and a watch, a rooster, plants, a tree, and an angel. Revere’s Day Book shows he charged Simon Willard, Aaron’s older brother, “six shillings for 100 prints for ‘Your Br Aron [sic] for Watches.’”3 The American Antiquarian Society [AAS] owns three copies of the Willard watchpaper. On the verso of one it reads “Oliver Jackson repair […] $1 […] May 28, 1817.” The AAS has several other Revere watchpapers but for tall clocks not pocket watches.4

The earliest known example of watchpaper printing in America was either in a watch sold by watchmaker, Samuel Bagnall of Boston, in 1740 or 1741 5 or printed by Hugh Gaine of New York in 1758. Gaine was also “among the first of many printers who pursued a lucrative new trade in attractive children’s books.”6

A narrow encircling margin would be printed with the shopkeepers’ ads, announcing sideline businesses like fishing tackle maker or umbrella repairs. Some margins would have numbers on the rim of the paper to allow the watch owner to set or compare the time against the local sun dial. As an example, one says, “Set W (watch) Slower then y Sun, Set Wat (watch) Fafter y (then) y Sun. ….. etc.”7 These margins were often snipped to enable fitting into the concave watch back.

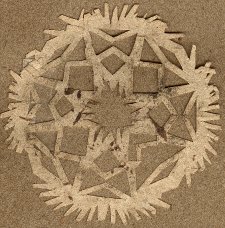

As engravers were more able to print miniature text, the watchpapers became more fanciful. The entire Lord’s Prayer or Ten Commandments could be included on the 1.5” to 2” discs, sometimes requiring a magnifying glass to read. The text could get so small it would go unnoticed allowing for secret messages, often of love. They might even be in rebus-style. Besides embroidered silk, the art of paper cutting was also used for embellishment. This was especially true in America where the Pennsylvania Dutch drew on their tradition of intricately cut paper for symbols of affection. In the Victorian tradition, locks of hair, sometimes woven, could be sequestered with the watchpaper.

Like learning a new word and then seeing it everywhere, I recently read of an auction of early 19th century watches, where several automatons had risqué “seesaw” and “concealed erotic” mechanisms. One sold for $218,000.8 We don’t have to understand the technical side of watchmaking to imagine the use of “seesaw” and “erotic” in the same sentence.9

My enthusiasm for this recent find has not waned. I continue to show it to a select group of visitors, all over 21 of course! As with any piece of ephemera, the fact that it survives at all is testimony to its uniqueness or its value to the owner. Watchpapers were almost ubiquitous but the British Museum has a mere 938 examples, none of them movable I might add.10,11

I can fantasize any number of scenarios about the owner of my little piece of ephemeral erotica, when he looked at it, and with whom he shared it. My collection has several very-hard-to-come-by examples of movable erotica. I’ve learned to ask for them without dropping my eyes or my voice. Hopefully, I will find more without traipsing into dark corners.

See additional images at the end.

Special thanks to Jaclyn Penny, Graphics Arts Assistant of the American Antiquarian Society, for her invaluable help and to Sheryl Jaeger of Eclectibles and Richard Newman for their generous loan of images.

1. The Encyclopedia of Ephemera, Maurice Rickards, Routledge, 2000, p.354.

2. http://www.theantiquesalmanac.com/watchpapers.htm [May 26, 2011]

3. Paul Revere’s Engravings, Clarence S. Brigham; Atheneum; New York, 1969, pp. 176 and 179; Revere Collection, American Antiquarian Society, Worcester MA.

4. http://www.americanantiquarian.org/Inventories/Revere/b1.htm andhttp://www.americanantiquarian.org/Inventories/Revere/b3.htm

5. Confessions of a Bookplate Junkie, May 24, 2011.

6. Of Sin and Salvation: Early American Children’s Books at Princeton; Dale Roylance; Princeton University Library Chronicle, Vol. LIX No. 2, Winter 1998, p221.

7. http://www.theantiquesalmanac.com/watchpapers.htm [May 26, 2011]

8. Antiques and the Arts Weekly, February 11 and April 22, 2011.

9. See more erotic watches [May 26, 2011]

10. The British Museum collection of watchpapers [May 26, 2011]

11. Go to bibliodyssey.blogspot.com for wonderful watchpaper examples.

From the Collection of the British Museum [below]