Pop-up and Movable Books In the Context of History

by Ellen G.K. Rubin

(from the catalog of Ideas in Motion exhibit @ SUNY-New Paltz, NY April, 2005)(see also A Timeline History of Movable Books )

The Chinese proverb, “I hear and I forget; I see and I remember; I do and I understand.” may well have served as the guiding principal for the inclusion of movable paper in books and ephemera. The use of wheels, flaps, turn-ups, pull-tabs, and pop-ups grabs the reader’s attention and ensures active participation. Whether intended for teaching, entertainment, or aesthetic sensibility, the use of movable paper devices demands the reader interact with the book’s content and makes the experience more memorable.

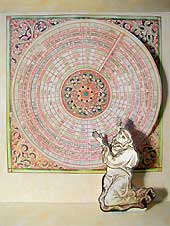

photo courtesy of Robert Sabuda

Books with mechanical elements date back to the 13th century and were originally created as teaching tools for adults. Matthew Paris, a English Benedictine monk, devised what is believed to be the first movable paper device, a volvelle, for his Chronica Majorca (1236-1253) to calculate the dates of Christian holidays for years to come. From the Medieval Latin verb, volvere, to turn, volvelles are overlaid printed circles of paper or parchment, rotating around a knotted linen string or rivet. They were used for religious calendars, for mathematical, scientific, and astronomical calculations, and as navigational aids. By turning the circles one over the other and lining up various information, data can be collated and new facts extracted.

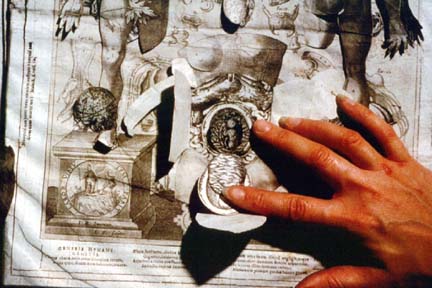

The invention of movable type by Johannes Gutenberg in 1450 allowed for the inexpensive printing of books and the wider proliferation of knowledge. In 1543, Andreas Vesalius published his landmark book, De corporis humani fabrica libri septem. Vesalius used innovative paper devices called flaps or fugitive sheets. The book was printed with woodcut illustrations of muscles, bones, and viscera arranged in layers. As each illustrated flap was lifted, the layer beneath it was revealed. Thus, the body’s internal organization became apparent. (Pages with flaps were often not bound into the books and were subsequently lost, hence, fugitive.)

photo courtesy of Carol Barton

For the first time, interested readers, including surgeons, barbers, medical students, and lay people, could have the hands-on experience of investigating the human body.

Before the 1800s in Western Europe, books were not written specifically for children’s enjoyment. Children were considered “amoral savages” needing to be taught right from wrong. The earliest illustrated books were moral tales of children meeting grisly fates for misbehavior. These attitudes toward childhood began to change in the 18th century as children came to be seen as “rational beings” with distinctive needs. It became acceptable for learning to be a pleasurable experience, with illustrations supporting the text, and for books to be read merely for the fun of it.

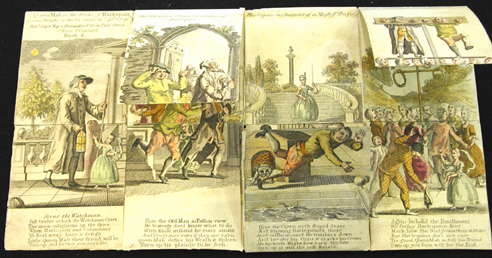

In 1765, the publisher Robert Sayer produced the first of a series of movable books expressly for children. These simple pamphlet-like books had split-page illustrations. When a part of the illustration was lifted either up or down, a new illustration was formed, advancing the story line. The “pamphlets” were referred to as “turn-up” or “metamorphosis” books or “Harlequinades,” after the Harlequin character featured in the stories.

Much was happening in England at this time to foster the proliferation of reading among children. The Industrial Revolution was getting into full swing, creating both middle-and leisure classes with money to spend on luxuries, like movable books. The Sunday School Movement of 1780, the First Public Libraries Act of 1850, and the Education Act of 1870, which established compulsory education in England, helped to create a literate populace. The success of Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe (1719) and Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels (1726) and later stories by the Grimm brothers (1823) and the English translation of Hans Christian Andersen in 1846 began a wave of children’s literature that continued into the early 20th century.

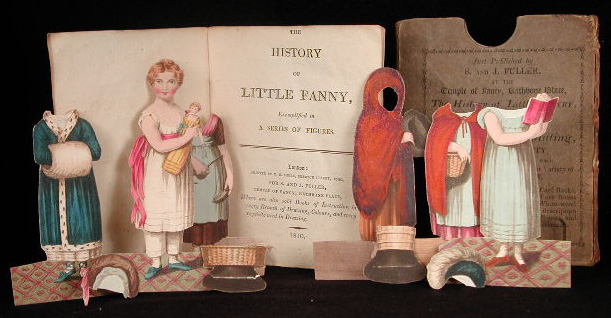

The consequence of all this was that English publishers began targeting the juvenile market. S & J Fuller printed The History of Little Fanny in 1810, the first paper-doll book with movable paper clothes. Dean & Sons, credited with being the first to devise three-dimensional illustrations in the 1850s, began printing almost 50 different titles with other varied and inventive movable elements, such as “peepshows,” transformations, and metamorphoses. Other publishers, especially Darton & Son, Ernest Nister of Nuremberg, Germany, and Raphael Tuck & Sons, also began producing illustrated and movable books.

Books for children, no longer puritanical and didactic, were widely translated into many languages. Germany became the center of printing, toy making, and hand-assembly. McLoughlin Brothers and E. P. Dutton in the United States began producing movable books of their own. Trade and friendship cards and postcards were also being printed using interactive devices. The increased production of illustrated reading material with animated elements was facilitated by the use of chromolithography, cheaper paper, and an organized labor force necessary for hand-assembly.

At the end of the 19th century, movable books were being printed in greater quantities than ever before. In this Victorian world without radio, television, or PlayStation, these unique books were a form of entertainment enjoyed by the whole family together. This distinctive time in publishing is often referred to as the Golden Age of Movable Books.

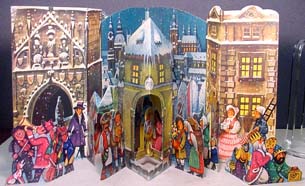

International Circus-1887

The paper engineer considered the “Genius” of this Golden Age was Lothar Meggendorfer (1847-1925) of Munich, Germany. Prolific, humorous, and inventive, his pull-tab books were the delight of adults and children around the world. Refining the use of rivets, he was able, with the pull of a single tab, to create multiple life-like movements. Meggendorfer also produced pop-up “theaters” of a circus, dollhouse, and city park. His satiric presentation of life’s little moments stood in stark contrast to the saccharine depiction of Victorian boys and girls seen in the Ernest Nister illustrations.

(animate Meggendorfer’s movables!)

It’s said, “All good things come to an end.” World War I destroyed the German production centers for printing and toy manufacturing. It became difficult to gather the manpower required to produce movable books, which were hand-assembled and labor-intensive. Paper production and the demand for ‘frivolous’ pastimes decreased as well. It would be over 50 years before these inventive books would again be in demand and published in large numbers.

Throughout this dearth of production between the World Wars, one man breathed new life into mechanical book publishing. It was Stephan Louis Giraud (1879-1950) of England, who patented a paper structure he variously called, “stand-up life-like,” “living models,” and “pictures that spring to life.” From 1929 to 1949, Giraud published both the Daily Express Annuals and then the Bookano Series, featuring three-dimensional structures that stood tall on the page when opened. They were the first true pop-ups.

The use of movables in books languished but did not completely die. America’s publishers and artists now joined England in greater numbers in using movable structures and devices in books, advertising, and greeting cards. In 1932, during the doldrums of the Depression, a New York company, Blue Ribbon Press, produced a series of pop-up books of classic fairytales and cartoon characters, such as Popeye, Dick Tracy, and Little Orphan Annie. It was Blue Ribbon Press that coined the term, ‘pop-up,’ and used it in their titles.

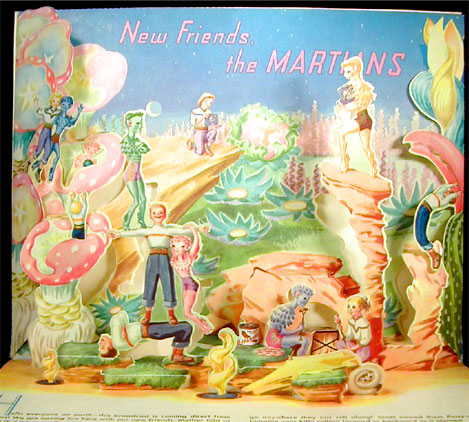

Providing much merriment and diversion during WWII was Julian Wehr of Brooklyn, New York. He patented a paper rocker panel that sat behind the base page and allowed for multiple movements with a single tab, much like Meggendorfer’s but without the use of a rivet. Also from New York was Geraldine Clyne who produced the Jolly Jump-up series from the late 1930s to the 1950s. She used fan-folded pop-ups, which are simple accordion, cut-and-folded illustrations. Her subjects ranged from the poetry of Robert Louis Stevenson, to life-styles in the new suburbia, to the imagined frontier of space travel. (animate Wehr’s movables! clowns & acrobats)

photo by James A. Findlay

The course of pop-up books took a major turn in the mid-1960s when the American entrepreneur Waldo Hunt of Graphics International almost single-handedly launched a Second Golden Age of Movable Books. While in Europe, he came upon the pop-up books of Vojtěch Kubašta of Prague, Czechoslovakia. Kubašta’s highly inventive pop-ups, brightly colored with faux naif-style illustrations, were being translated into 37 languages and distributed by Westminster Books of England with great success in Europe, Asia, and the Middle East. Hunt’s proposal to distribute Kubašta’s books in the United States was rejected by Artia, the Soviet producer, because Hunt’s large order wouldn’t fit into the Communists’ Five Year Plan! Hunt went back to America and put together a remarkable team of pioneering paper engineers, chiefly, Ib Penick, Tor Lokvig, and John Strejan. With Random House, he published Bennett Cerf ’s Pop-up Riddle Book (1965) and gave it away as a Maxwell House Coffee premium. Random House went on to produce a series of pop-up and movable books into the 60s and 70s as did Hallmark Cards, which later took over Graphics International. Hunt, in 1976, formed the packaging company, Intervisual Books. It produced many of the pop-ups we consider classics today.

Innovations in paper engineering continue to be made. In 1992, Ron Van der Meer began his multi-media series with The Art Pack, emphasizing movable paper’s unique ability to teach by drawing upon the reader’s active participation. Included in each book were audio tapes, removable booklets and pop-ups, and text behind gatefolds. Robert Sabuda, using solely white paper in his first pop-up book, The Christmas Alphabet(1996), stressed the sculptural aspects of three-dimensional paper and continues to dazzle readers with evermore complex pop-up surprises. Kees Moerbeek, after 25 years of searching, found a format for his unique roly-poly pop-ups. The Caldecott-winning illustrator, Paul O. Zelinsky, teamed up with the Meggendorfer Prize-winning paper engineer, Andrew Baron, to create today’s most complex movable book, Knick-Knack Paddywhack (2003), with over 200 moving parts!

In the last few years, the number of titles of pop-up books printed has waned. Movable books are still hand-assembled, and publishers and packagers continually seek the least costly labor forces, now primarily in Asia. It’s hard to say if the downturn in titles is a consequence of the vagaries of the current marketplace, the shrinking number of publishers, or the books’ ever-increasing costs, largely based on labor, glue-points and paper use. What clearly has not changed in over 700 years is that pop-up and movable books are still the products of inspired artists, still have a unique ability to teach, and are still loved by adults and children alike.